Last week, we enjoyed taking the Gold Rush City Walking Tour through San Francisco City Guides. The tour is a great opportunity to celebrate the role of the gold rush in San Francisco. After enjoying it, we wanted to take this opportunity to write a bit about San Francisco’s position as a stage for the beginning of the California Gold Rush and how, in turn, the rush transformed the city.

While San Francisco has always had a well sheltered bay for shipping, it blossomed into a city with the California gold rush. Originally known as “Yerba Buena” by the early Spanish settlers, it was still a small town of less than 500 people right before the gold rush began. It only came into the hands of the US government in 1848, with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Yet, in that same year aspiring prospectors from around the world would travel to California through the port of San Francisco.

Gold had been discovered a few times in California before the rush, but not with the fanfare that occurred in 1948. Even the gold in Sutter’s Mill might not have gained the notoriety it did if not for a newspaper man in San Francisco. Samuel Brannan heard about the gold in the California foothills and returned to San Francisco and his printing presses to spread the word (after conveniently cornering the market for picks, shovels, and other prospecting tools). As other newspapers picked up Brannan’s excited announcement, the rush was on.

Aspiring prospectors flooded the city. While those who traveled overland in wagon trains made a beeline for the gold fields. Those who took the more convenient sea routes entered California through the San Francisco bay. The city expanded to service the arriving prospectors headed to—and the new wealth that was coming out of—the gold fields. Real estate prices skyrocketed so that only highly profitable establishments (often pubs, brothels, and gambling joints) could afford to operate in the main part of town, near the docks.

The gold rush was so alluring that ships entering San Francisco bay not only unloaded passengers and cargo but often their entire crews. Ship’s hands would abandon their duties to seek their fortune in the gold fields. With no way to return to the original ports, the crewless ships were often sunk into the bay.

Not all ships were sunk, though. Ships crews were not the only manpower that was abandoning their positions for a chance to strike it rich. With the limited resources and manpower available, rather than building shops on land, some ships were converted into floating hotels, shops, and other businesses. The Niantic is one such ship, which was converted into a hotel. Some of these businesses experienced such success that they eventually did build shops on land, such as the City of Paris, last located on the current site of Neiman Marcus in Union Square.

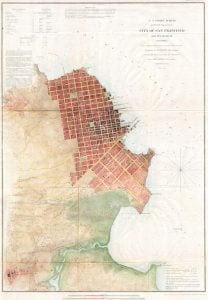

by the U. S. Coast Survey

Walking along these streets of old San Francisco, visitors will encounter plaques marking locations of sunk ships. These locations can now be accessed on foot because the shore line of San Francisco has changed dramatically over time. There are many reminders of where the the old shoreline used to be, including Montgomery street, which used to run along the shore line. Much of this changing shore line was also due to the gold rush.

While there was so much wealth flowing through the town, developing it was also difficult because of the steep hillsides of San Francisco. Rather than building on these inclines and seizing an unconventional opportunity, the city began selling off portions of land that was, as of yet, underwater. Entities that purchased these more affordable, though not yet usable patches of land, began fencing off their property lines and filling in the land with garbage and rubble. Much of San Francisco’s current waterfront is landfill.

Many individuals did not need to dig in the gold fields to get rich from the California gold rush. Men such as Brannan made fortunes selling goods to miners. Between his newspaper and businesses, Brannan became California’s first millionaire. Levi Strauss, who came out to California as a miner but stayed as a merchant, sold durable pants that could hold up against the rough life a miner. The first blue jean. Levi Strauss & Co., is still headquartered in San Francisco Other businesses flourished, providing alcohol, cards, and women to lonely, young men.

San Francisco, from its inception, became a deeply international city, as the individuals from around the world who had been attracted by gold, settled in the city. The diversity of restaurants now in the city is testament to the diversity of those ambitious souls who left their homes and families in the mid 1800s for the promise of gold in California.

You can learn more about San Francisco and points of interest for the gold history enthusiast by taking the Gold Rush City Walking Tour through San Francisco City Guides. Learn more at: http://www.sfcityguides.org/desc.html?tour=37

Related Mines

While we don’t have mines listed in San Francisco, we certainly have plenty claims listed the gold fields that catalyzed the city: